Devon Tour

Flete, Mothecombe, Shilstone, Castle Drogo

26 April 2013

Our two-day visit to Devon began by visiting Flete, a magnificent country house now leased to Audley Court Ltd as a retirement home. David Sparkes, the administrator for the home, gave us an enthusiastic tour of the public rooms on the ground floor.

Untouched by Lutyens I hasten to add, what remained of a derelict Jacobean manor house was radically enlarged by Norman Shaw in 1877. The client was Henry Mildmay who had bought it two years previously. He was a partner of Barings, and consequently Shaw’s richest client. It appears, however, he proved a difficult client, as he would not allow Shaw to demolish the whole house and start again. Consequently, the rebuilding had to be carried out in phases, and the plan was to be unsatisfactory to him. In addition the Mildmays had in mind that this was to be a castle, and thus there are none of the huge gables that we associate Shaw with, but crenellated parapets instead.

Despite this, Shaw creates some typically sumptuous interiors, such as the entrance hall with its magnificent staircase, and the library with a baldacchino fireplace of marble and stained glass windows by Burne Jones.

The dining room is also of note, as Shaw salvaged two very fine medieval pillars and used them to frame a huge new granite fireplace. Shaw fell ill at one point, and some of the interiors were designed by William Lethaby. The contractor was Frank Bircham of Farnham, and the clerk of works Ernest Newton. However, there is an important connection with Lutyens as he did visit Flete in l9l0 with Cecil Baring when Julius Drewe was commissioning Castle Drogo.

Lutyens called it “a great house built by Shaw 31 years ago”, but awfully nouveau riche – Shaw elaborated too much of it and old Aldam Heaton has done the decorating – oak yellow – carbed and the ceilings, carpets, walls and everything were agog with patterns – a pity”. Nevertheless, there is precedent for Drogo here, as Bridget Cherry notes in the Devon Pevsner, the crenellations on the entrance front “rising sheer and dour without any restraining horizontal cornice” did offer a device, which Lutyens uses at Castle Drogo.

Our next visit, down a tangle of country lanes, led us to Mothecombe House, which is also part of the Flete Estate. On our arrival we were all bowled over by a classical facade built in silvery-grey ashlar granite, contrasted with small paned white painted sash windows and a white cornice to the eaves.

Built around 1720, it is typical of the post-restoration format; five bay front, two storeys over a basement, and attics with dormers set in a big hipped roof. High brick walls enclosed the forecourt containing an oval carriageway, fronted with fine painted palings and gates. Set on a sloping site, on the side of a secluded valley, its location hides it away from public view. Lutyens found it a “delicious place” in 1910.

Our hosts’ Mr. and Mrs. Anthony Mildmay-White, very kindly showed us around their delightful home, pointing out all the alterations that Lutyens had made. Some of which are not without controversy perhaps, for it was in the front hall that he redecorated over a painted frieze by Morris, no less – in, yes you’ve guessed it, black. Of course, it works brilliantly, contrasting very well with white painted panelling beneath. But what was even bolder was to paint the entire grand central timber staircase in black too – in gloss of course (I rook for-ward to proposing the same myself, one day). Fortunately, perhaps, Lutyens chose olive green for the drawing-room and library and his original colour scheme survives.

These alterations were at the behest of Alfred Mildmay, back in 1922, who asked Lutyens to generally improve the house. This included the installation of electricity, central heating and structural repairs, together with the reinstatement of the small-paned sash windows with fat glazing bars typical of the period. However, his main contribution to the house was to replace an annex of 1873, with a single storey range, over an undercroft, containing a dining room. The dining room, with a high coved ceiling of double cubed proportions, is set apart from the main house with a lower link, containing a corridor, and thus restores the formal facade overlooking the garden. The external walls are built in a very attractive green Tavistock stone, but which is apparently prone to frost damage. Fortunately, the owners have continued to carry out a number of sensitive repairs. The corridor contains a groined vault, which is cranked as it turns towards the dining room, but that is where simplicity ends and genius takes over, for Lutyens creates an illusion of greater length by narrowing each end with an arrangement of diminishing arches – pure joy. A cupboard, containing a butler’s sink is lined in mirrored black glass.

Again, Lutyens found inspiration at Mothecombe, using the coved cornice and pilasters in his 1911 – 12 design for Ednaston Manor in Derbyshire.

Then it was onwards again, without pausing for breath, to Shilstone Manor – miraculously found without satnav. A very welcome lunch was provided for us on arrival, followed by a slide show presentation by the owner Mr. Sebastian Fenwick, after which he then proceeded to take us on a tour of his home.

And what a home. what was a medieval manor house originally, with fish ponds in the grounds, had been remodelled in the eighteenth century with much of the original manor demolished. Mr. and Mrs. Fenwick recognised its potential, and undertook careful archaeological research before embarking on an extensive remodelling programme with their architect Christopher Rae-Scott. The house is now greatly extended, and faithfully copies different period styles to give the impression of building over time. For example, the garden elevation has distinct elements to look like they were built in 1600, 1690, and 1730 – everything I was told not to do at my school of architecture.

Despite what one may say about a resulting pastiche, there is no doubt that the detailing here is very fine, and the top quality craftsmanship gives a result of deserving merit. New stone for the external walls was even quarried from the estate itself, and the extensive internal joinery is extremely handsome.

There was, however, one piece of particularly fine furniture of interest to us, a St Ursula’s bed, designed by our man. And, the connection does not end there, for it was Sebastian Fenwick’s grandfather, Mr. and Mrs. H. G. Fenwick who commissioned Lutyens to remodel Temple Dinsley, and Edwin was godfather to Sebastian’s father.

Such is Mr. Fenwick’s enthusiasm for traditional craftsmanship and the vernacular architecture of Devon, that at Shilstone he has set up the Devon Rural Archive where they aim to research as many of Devon’s traditional buildings as possible.

Our thanks to David Sparkes, Mr. and Mrs. Mildmay-White, and Mr. and Mrs Fenwick for giving us such an enjoyable day.

The next day dawned another fine sunny day, as we mustered inside the visitors’ centre at Castle Drogo. After a welcome speech by Steve Mulberry, the General Manager, we were split into two groups – one to visit the castle, whilst the other was given a tour of the gardens; having never been here before I was keen to go round the castle first.

Our guides to the castle were Bryher Mason (House and Collections Manager), and Tim Cambourne (Project Manager). They gave us a fascinating tour through the south wing, which is to comprise the first phase of the refurbishment. The library had already been dismantled, and items of furniture stored away or relocated to other parts of the castle. The castle remains open to the public, as far as possible, despite features being boxed over with protection.

Down the main staircase, with its spectacular bay window (slightly bowing outwards, but nothing to worry about), and into the dining room, where a full size mock-up model, explained the construction of the walls and floors. Tim pointed out the layer of asphalt applied to the outer face of the inner skin of granite walling, and that this had formed a continuous layer with the asphalt under the granite slabs of the flat roofs. Being a novel material at the time, it was not completely understood – it failed to accommodate the thermal expansion of the concrete substrate adequately, and in the walls it denatured, thus allowing water to penetrate. In the 1980s matters were made worse when the castle was extensively repointed in hard cement pointing; this literally dammed the water, only allowing it to escape internally. Apparently, Lutyens had wanted to maintain a cavity wall construction, but such was the client’s wish for real solid walls, that the inner core was fully filled with mortared rubble.

Through the wonderful kitchen, with its pendentive ceiling, circular lantern, and circular table. Upwards and into the private flat of the donor family, kindly given permission by Patrick Johnstone (a descendant of Julius Drewe by marriage) who was also present to show us around. And finally up onto the roof, which, although flat, changes level at every turn.

Magnificent views abound across Devon. And down into the Teign valley beneath – a dramatic setting indeed. The whole roof is to be taken up, and an insulated warm roof installed with a modem Bauder waterproof membrane, before reinstating the granite slabs. The battlements are also to be taken down and rebuilt with a modem damp proof course, whilst the 64km of mortar joints to the external elevations are to be repointed in a lime mortar.

Extensive trials have been undertaken, and the Bauder system successfully installed on the Chapel three years ago – such is their faith that the Chapel is being used as a store room, and was consequently not available to us to visit.

Running late, we descended to ground level, and back to the visitors’ centre for a hearty lunch, before swapping over for the other half of the tour. At this point my nerve left me as I was keen to go back to the castle and visit the remaining public rooms we had not managed to see (the fact that I had been asked to write up these notes completely escaped me).

So back into the castle and a detour to the left led me into another staircase, corridors, bedrooms and bathrooms. The whole building is an amazing testament to three-dimensional complexity and spatial planning at which Lutyens was so adept – I’m sure this was added to by the National Trust’s ability to rope off certain areas.

At one point I owned up to being lost, and helped by a guide across one such rope I re-joined my surrogate group to their great surprise. However, it was not long before I noticed Martin Lutyens through a window on the garden tour, which was being conducted by the Head Gardener, John Rippin and I thought this was my chance to join them.

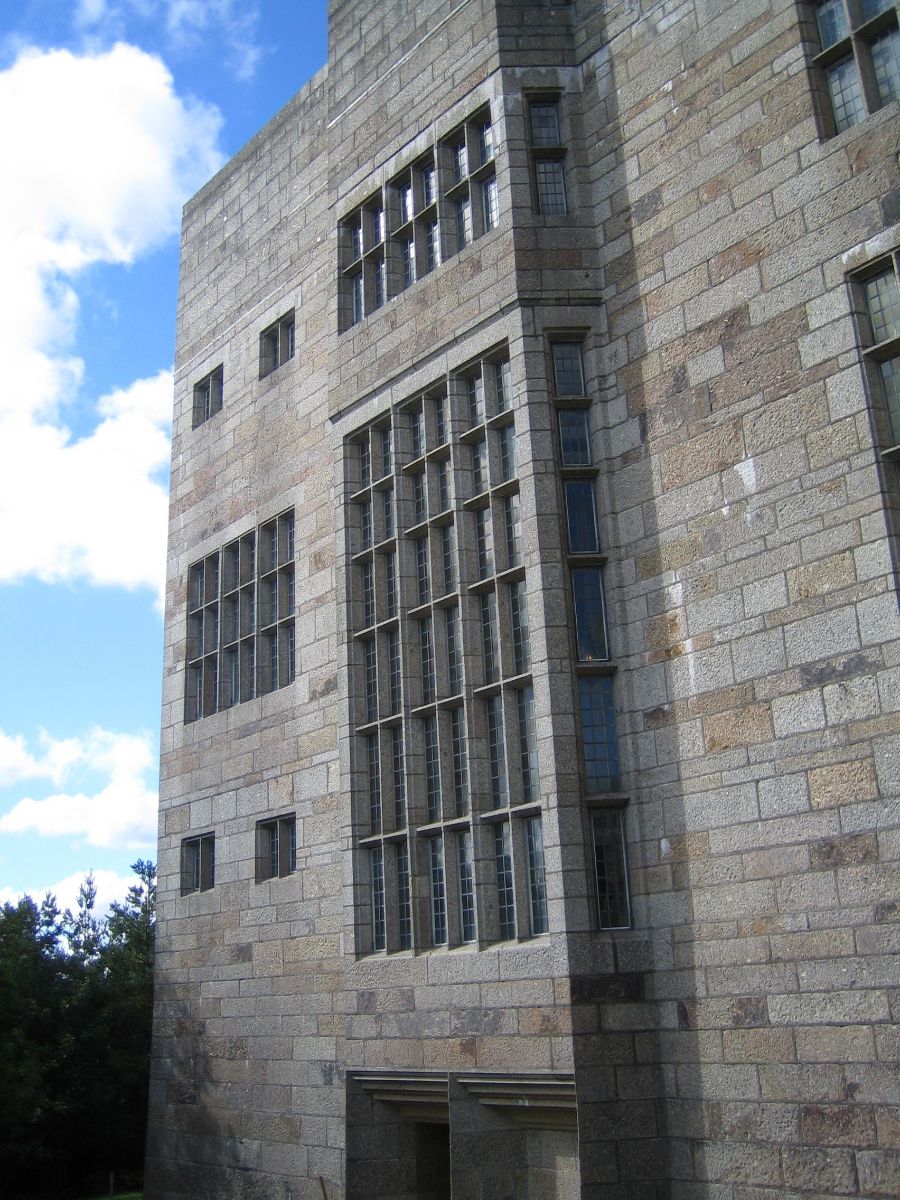

Popping out at the base of these great walls I joined them looking up at the precipitous southern elevation rising four storeys. Set beside the chapel this elevation is the most abstract and powerful – no namby-pamby crenellations here, but razor-like ears instead – very severe, but breathtakingly dynamic.

Tearing myself away from the castle, we walked up to the formal garden, which, unusually, is set some distance away from the castle. Despite not being the best time of year to visit the garden, it is still striking as it is enclosed in high architectural yew hedges, with four yew rooms one at each comer roofed in with Persian Ironwood trees pleached over steel arbours. The layout is rectangular and symmetrical about a central axial path. There are terraces on three sides, faced in rubble granite, the flanking terraces have the distinctive serpentine path which Lutyens must have brought back from India. A further terrace at the end is built of dressed granite, upon which is laid an enormous wisteria. Up the double flight of steps, the central path continues, planted each side in a more informal fashion with azaleas, cherries, and magnolias, also yet to blossom, and beyond that is a huge round lawn walled in yew again. An archaeological survey has been done of the estate surrounding Castle Drogo and John Rippin explained the Trust’s aim that the garden and house should be considered as a single concept, a castle set in a wild landscape.

Reluctantly we returned to the visitors’ centre where cream teas awaited. Martin Lutyens thanked Bryher Mason, Tim Cranbourne and John Rippin for hosting such a wonderful day. The Lutyens Trust has long been supporting the National Trust Appeal for the restoration of Castle Drogo which will amount to nearly £11 million of which the National Trust has funded £7 million from general funds and the remainder from the public matched by the Heritage Lottery Fund and other charities. The Lutyens Trust has helped with a series of events and on this occasion Martin presented to Bryher Mason a cheque for the fund from all the members of the Trust. Bryher expressed her gratitude to all members of the Lutyens Trust for their support.

Our thanks again to all our hosts over the two days, and especially to Janet Allen for all her hard work in organising the tour and producing such informative notes.

Ashley Courtney

Follow us on X

Follow us on X Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on YouTube

Follow us on YouTube